Education of the All-Russian market. All-Russian market

A prerequisite for the formation of an all-Russian market was the regional division of labor. Moscow by this time had become the most important transport hub, a center for the intersection of trade routes, and was of exceptional importance for the formation of the all-Russian market.

Let us trace the movement of goods of that time. Meat and vegetables were supplied to Moscow from the Moscow region. Cow butter was brought from the Middle Volga region. Pomorie, Rostov district, Lower Volga region and the Oka region constantly supplied fish. Vegetables also came from Vereya, Borovsk and Rostov district. Moscow was supplied with iron by Tula, Galich, Zhelezopolskaya and Tikhvin; leather was brought mainly from the Yaroslavl-Kostroma and Suzdal regions; wooden utensils were supplied by the Volga region; salt - cities of Pomerania. Traditionally, Moscow has been the largest market for Siberian furs.

Based on the production specialization of individual regions, markets were formed with the predominant importance of certain goods. In Yaroslavl, leather, soap, lard, meat and textiles could be sold well. Veliky Ustyug and especially Sol Vychegda were the largest fur markets - furs coming from Siberia were delivered from here either to Arkhangelsk for export, or to Moscow for sale on the domestic market.

Smolensk and Pskov were considered centers of trade in flax and hemp, since these goods were produced in nearby areas and then entered the foreign market.

Some regional markets turned into trading centers for one or another traditional type of product that was important for the entire country. Intensive trade relations were established with cities far removed from them. For example, Tikhvinsky Posad with its annual fair supported trade with 45 cities of Russia. Buying cheap iron-making products from local blacksmiths, buyers resold them to larger traders. The latter transported significant quantities of goods to Ustyuzhna Zhelezopolskaya, as well as to Moscow, Yaroslavl, Pskov and other cities.

In addition to specialized regional markets, fairs of all-Russian significance played a major role in the country’s trade turnover, such as Makaryevskaya (near Nizhny Novgorod), Svenskaya (near Bryansk), Arkhangelsk, etc. Such fairs were characterized by an abundance of goods and trading at them continued for several weeks .

The emergence of the all-Russian market increased the role of the merchants in the economic and political life of the country. In the 17th century, the top of the merchant world stood out more and more noticeably from the general mass of trading people. The state encouraged individual representatives of the merchant class by assigning them the title of guests. These largest merchants became financial agents of the government - on its instructions they carried out foreign trade in furs, potash, rhubarb, etc. The functions of merchants bearing the title of guests included carrying out construction contracts, they also purchased food for the needs of the army, collected taxes, customs duties, tavern money, etc. Guests attracted smaller merchants to carry out contracting and farming operations, sharing with them huge profits from the sale of monopoly goods: wine and salt. State farm-outs and contracts provided an opportunity for the accumulation of capital, which large merchants could then invest profitably.

Quite large capitals accumulated in the hands of individual merchant families. Thus, the merchant N. Sveteshnikov owned numerous salt mines. The Stoyanovs in Novgorod and F. Emelyanov in Pskov were among the first people in their cities. Owning entire fortunes, they could influence not only the governors, but also the tsarist government. The guests, as well as merchants close to them in position from the living room and cloth hundreds (associations), were joined by the top of the townspeople, called the “best”, “big” townspeople, who enjoyed authority in the merchant environment.

Trade in a country in which trades were slowly but steadily developing and there were huge reserves of raw materials formed a new class in society. Having significant capital, the merchant class begins to speak before the government in defense of its interests. In petitions they asked to limit, or even completely ban, English merchants from trading in Moscow and other cities, with the exception of Arkhangelsk. The petition was granted by the royal government in 1649 under the pretext that the British had executed their king Charles I.

The fact that significant changes had occurred in the country's economy was reflected in the Customs Charter of 1653 and the New Trade Charter of 1667. For political reasons, the head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz, A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin, took part in the creation of the 1667 charter. He understood the needs of the Russian merchants well and took them into account when justifying customs duties on foreigners, while also respecting state interests. It is curious that in the 17th century, many European countries were characterized by mercantilistic views on issues of international trade. Russia is no exception among them. The New Trade Charter noted the special importance of trade for Russia, since “in all neighboring states, in the first state affairs, free and profitable trading for the collection of duties and for the people’s worldly belongings is guarded with all care.”

The Customs Charter of 1653 abolished a number of small trade fees that had persisted since the time of feudal fragmentation, and in their place introduced one so-called trade duty - 10 kopecks each. from a ruble for the sale of salt, 5 kopecks. from the ruble from all other goods. As for the duties for foreign merchants selling goods within Russia, in the interests of the Russian merchants, the New Trade Charter of 1667 further increased customs duties on them.

In the 17th century, the most profitable and prestigious industry was foreign trade. Thanks to her, the most scarce goods were supplied from the Middle East: jewelry, incense, spices, silk, etc. The desire to have it all at home stimulated the formation and further strengthening of our own production. This served as the first impetus for the development of internal trade in Europe.

Introduction

Throughout the Middle Ages, there was a gradual increase in the volume of foreign trade. Towards the end of the 15th century, the result of the series was a noticeable leap. European trade became global, and smoothly transitioned into the period of initial capital accumulation. During the 16th-18th centuries there was a strengthening of economic interaction between a number of regions and the formation of national trading platforms. At the same time, the formation of national states of absolute centralized monarchies is noted. The entire economic policy of these countries was aimed at the formation of a national market, the establishment of foreign and domestic trade. Great importance was also attached to strengthening industry, agriculture, and communications.

The beginning of the formation of the all-Russian market

By the 18th century, new regions gradually began to join the sphere of universal trade relations of Rus'. For example, food and some industrial goods (saltpeter, gunpowder, glass) began to arrive in the center of the country. At the same time, Russia was a platform for selling products of local artisans and factories. Fish, meat, and bread began to arrive from the Don regions. Dishes, shoes, and fabrics came back from the central and Volga districts. Livestock came from Kazakhstan, in exchange for which neighboring territories supplied grain and certain industrial goods.

Trade fairs

Fairs had a great influence on the development of the all-Russian market. Makaryevskaya became the largest and had national significance. Goods were brought here from various regions of the country: Vologda, the west and north-west of Smolensk, St. Petersburg, Riga, Yaroslavl and Moscow, Astrakhan and Kazan. Among the most popular are precious metals, iron, furs, bread, leather, various fabrics and animal products (meat, lard), salt, fish.

What was purchased at the fair was then distributed throughout the country: fish and furs to Moscow, bread and soap to St. Petersburg, metal products to Astrakhan. Over the course of the century, the fair's turnover increased significantly. So, in 1720 it was 280 thousand rubles, and 21 years later - already 489 thousand.

Along with Makaryevskaya, other fairs also acquired national significance: Trinity, Orenburg, Blagoveshchensk and Arkhangelsk. Irbitskaya, for example, had connections with sixty Russian cities in 17 provinces, and interaction was established with Persia and Central Asia. was connected with 37 cities and 21 provinces. Together with Moscow, all these fairs were of great importance in uniting both regional and district, as well as local trading platforms into the all-Russian market.

Economic situation in a developing country

The Russian peasant, after his complete legal enslavement, was, first of all, still obliged to pay the state, like the master, a quitrent (in kind or in cash). But if, for example, we compare the economic situation of Russia and Poland, then for Polish peasants conscription in the form of corvee became increasingly stronger. So, for them it ended up being 5-6 days a week. For the Russian peasant it was equal to 3 days.

Payment of duties in cash presupposed the existence of a market. The peasant had to have access to this trading platform. The formation of an all-Russian market stimulated landowners to run their own farms and sell products, as well as (and to no lesser extent) the state to receive fiscal revenues.

Economic development in Rus' from the 2nd half of the 16th century

During this period, large regional trading platforms began to form. By the 17th century, the strengthening of business ties was carried out on a national scale. As a result of expanding interactions between individual regions, a new concept is emerging - the “all-Russian market”. Although its strengthening was to a large extent hampered by the Russian chronic impassability.

By the middle of the 17th century, there were some prerequisites due to which the all-Russian market arose. Its formation, in particular, was facilitated by the deepening social division of labor, production territorial specialization, as well as the necessary political situation that emerged thanks to the transformations that were aimed at creating a unified state.

The main trading platforms of the country

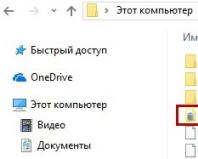

From the 2nd half of the 16th century, such main regional markets as the Volga region (Vologda, Kazan, Yaroslavl - livestock products), the North (Vologda - the main grain market, Irbit, Solvychegodsk - furs), North-West ( Novgorod - sales of hemp and linen products), Center (Tikhvin, Tula - purchase and sale of metal products). Moscow became the main universal trading platform of that time. There were about one hundred and twenty specialized rows where you could buy wool and cloth, silk and fur, lard and metal products of both domestic and foreign production.

Influence of state power

The All-Russian market, which emerged as a consequence of the reforms, contributed to an increase in entrepreneurial initiative. As for social consciousness itself, ideas of individual rights and freedoms arose at its level. Gradually, the economic situation in the era of initial accumulation of capital led to freedom of enterprise both in trade and in other industries.

In the agricultural field, the activities of the feudal lords are gradually replacing state regulations on changing the rules of land use and farming. The government promotes the formation of national industry, which, in turn, influenced the development of the all-Russian market. In addition, the state patronized the introduction of agriculture, more advanced than before.

In the sphere of foreign trade, the government seeks to acquire colonies and conduct Thus, everything that was previously characteristic of individual trading cities now becomes the political and economic direction of the entire state as a whole.

Conclusion

The main distinguishing feature of the era of initial accumulation of capital is the emergence of commodity-money relations and a market economy. All this left a special imprint on all spheres of social life of that period. At the same time, it was a somewhat contradictory era, in fact, like other transitional periods, when there was a struggle between feudal control of the economy, social life, politics, spiritual human needs and new trends in bourgeois freedoms, due to the expansion of trade scales, which contributed to the elimination of territorial isolation and limitations of feudal estates.

The 17th century was marked by the most important event in the economic life of the country - formation of an all-Russian market. Certain prerequisites have emerged for this in Russia. As stated earlier, there has been an increasingly noticeable deepening in the country territorial division of labor. A number of areas specialized in the production of various industrial products. In agriculture, a certain regional specialization also developed; agricultural farms began to produce products for sale. In the north-west of Russia they preferred to grow flax for the market, in the south and south-east - bread and beef cattle, near large cities - vegetables and dairy cattle. Even monasteries were engaged in the production of various products for sale: leather, lard, hemp, potash, etc.

All this contributed to strengthening economic ties between regions and the gradual merging of local markets into one, all-Russian one. Moreover, the centralized state encouraged the process of such unification. Left Bank Ukraine, the Volga region, Siberia, and the North Caucasus were gradually drawn into economic ties.

If in the 16th century domestic trade was carried out mainly in small markets, then in the 17th century regular fairs began to appear (from German. Jahrmarkt- annual market). As a rule, they were held at certain times of the year for several days and even weeks, near large monasteries during major church holidays or in the fall, after the end of field work. Merchants from different cities and countries came here, wholesale trade took place here, and large trade and credit transactions were concluded.

All-Russian fairs emerged: Makaryevskaya(Nizhny Novgorod), Svenskaya(on the Sven River near Bryansk), Arkhangelskaya, Tikhvinskaya, Irbitskaya, Solvychegodskaya. Novgorod the Great, which was famous for trade back in the 11th-12th centuries, occupied a special place among shopping centers. Yes, the legendary guslar Sadko, who became a merchant, had a real prototype of Sotko Sytin, whose name is mentioned in the Novgorod chronicle of the 12th century, since he built the temple with his own money.

In Novgorod the Great, guest trade was carried out by artel-companies. One of these companies was known since the 13th century and was called " Ivanovo-sto"(by the Church of St. John the Baptist). She had a common gostiny dvor (goods warehouse), “ gridnitsa"(large chamber for holding meetings). The merchants who founded this company were waxworts, not only were engaged in the wax trade, but also actively participated in the political life of the Novgorod Republic. The company was led by an elected headman, who monitored order and the correctness of paperwork. The company had large special scales to check the accuracy of the weight of goods, and

Money bars were weighed on small scales. It had its own commercial court, headed by Tysyatsky, which resolved various conflicts. It was difficult to join the Ivanovo artel; for this you had to pay a fee of 50 hryvnia and donate 30 hryvnia of silver to the temple. With this money one could buy a herd of 80 cows. Later, membership became hereditary and was passed on to children if they continued the trading business.

Since the 15th century, the Novgorod merchants Stroganovs have become famous. They were among the first to start salt production in the Urals and traded with the peoples of the North and Siberia. Ivan the Terrible gave the merchant Anika Stroganov control over a huge territory: the Perm land along the Kama to the Urals. With the money of this family, Ermak’s detachment was later equipped to explore Siberia.

But in the 15th-16th centuries the center of trade gradually moved to Moscow. It was in Moscow in the 17th century that the merchants as a special class of city dwellers, playing an increasingly prominent role in the economic and political life of the country. Especially stood out here eminent merchants (“guests”), approximately 30 people. This honorary title was received from the tsar by those who had a trade turnover of at least 20 thousand rubles per year (or about 200 thousand gold rubles in the price scale of the early 20th century). These merchants were especially close to the kings, carried out important financial assignments in the interests of the treasury, conducted foreign trade on behalf of the king, acted as contractors on important construction projects, collected taxes, etc. They were exempt from paying duties and could purchase large plots of land. . Among such eminent guests in the 16th-17th centuries are G.L. Nikitnikova, N.A. Sveteshnikov, representatives of the Stroganov, Guryev, Shustov families and others.

Merchants with less capital were part of two trading corporations - living room And cloth"hundred". Their representatives also had great privileges and had elected self-government within the “hundreds,” which were led by “heads” and “elders.” The lowest ranks included "black hundreds" And "sloboda". This usually included those who produced the products and sold them themselves.

Foreigners who visited Russia in the 15th and 16th centuries were amazed at the scale of trade. They noted the abundance of meat, fish, bread and other products in Moscow markets and their cheapness compared to European prices. They wrote that beef is sold not by weight, but “by eye”, that representatives of all classes are engaged in trade, and that the government supports trade in every possible way. It is important to note that the Western European “price revolution” that took place in the 16th century also affected Russia. It is known that during the era of the Great Geographical Discoveries, huge amounts of cheap gold and silver from America poured into Europe, which led to a sharp depreciation of money and an equally sharp general rise in prices. In Russia, connected with Western Europe by economic relations, prices also increased by about three to four times by the beginning of the 17th century.

In the 16th-17th centuries in Russia, the process of initial accumulation of capital began precisely in the sphere of trade. Later, merchant capital began to penetrate into the sphere of production, rich merchants bought craft workshops and industrial enterprises. Along with patrimonial and state property, there appeared merchant manufactories, which used the labor of free townspeople, quit-rent peasants released to latrine trades, and foreign craftsmen were also involved. About 10 thousand free people were employed in various Stroganov industries (salt, potash).

One of the sources of accumulation of merchant capital was the system farm-outs, when the government granted rich merchants the right to sell salt, wine and other goods important to the treasury, and to collect tavern and customs duties. Thus, Moscow guests Voronin, Nikitnikov, Gruditsyn and others traded grain, had large iron factories, were ship owners, and were tax farmers for the supply of food and uniforms to the army.

In the 16th-17th centuries, Russia began to more actively develop foreign trade. Even under Vasily III, trade agreements were concluded with Denmark; under Ivan IV, strong ties were established with England. English merchants were given great privileges in trade, which was carried out practically without duties for both sides. The British founded several trading houses-factories in Vologda, Kholmogory, Moscow, Yaroslavl, Kazan, Astrakhan.

Bilateral Anglo-Russian relations date back to the mid-16th century, when English merchants began searching for routes to India and China across the Arctic Ocean. In 1553, three English ships found themselves stuck in the ice of the White Sea near the mouth of the Northern Dvina. Some of the sailors died, and the remnants of the expedition landed on the shore near the village of Kholmogory. The British, led by the commander of one of the ships, Richard Chancellor, were transported to Moscow to the court of Ivan the Terrible, where they were received with great honors.

Founded in London in 1554 Moscow company, which carried out not only trade, but also diplomatic relations between the two countries. England exported from Russia canvas, ropes, hemp, ship timber and other goods necessary for equipping its fleet. And for centuries, England occupied a leading place in Russia's foreign trade. And in Moscow, on Varvarka Street, the building is still preserved Old English Court (English Embassy), built back in the 16th century.

Following England, Holland and France rushed to the Russian market. Foreign trade was carried out on a large scale with Lithuania, Persia, Bukhara, and Crimea. Russian exports included not only traditional raw materials (timber, furs, honey, wax), but also handicraft products (fur coats, linen canvas, horse saddles, dishes, arrows, knives, metal armor, ropes, potash and much more). Back in the 15th century, a Tver merchant Afanasy Nikitin visited India 30 years before the Portuguese Vasco da Gama, lived there for several years, learned foreign languages, strengthened trade ties with eastern countries.

Foreign trade in the 17th century was carried out mainly through two cities: through Astrakhan there was foreign trade turnover with Asian countries, and through Arkhangelsk- with European ones. Arkhangelsk, founded in 1584 as a seaport, was especially important, although Russia did not have its own merchant fleet and all cargo flowed on foreign ships. In the middle of the 17th century, goods worth 17 million rubles were exported abroad annually through this port. gold (at prices of the early 20th century).

The Russian merchants were not yet able to compete in the domestic market with strong foreign companies, and therefore they sought to strengthen their monopoly position with the help of the state. Merchants in petitions asked the government to establish protectionist measures to protect domestic interests, and the government largely met them halfway. In 1649, duty-free trade with England was abolished. Introduced in 1653 Trading Charter, which imposed higher trade duties on foreign goods. By New Trade Charter 1667, foreign merchants were allowed to conduct only wholesale transactions in Russia and only in certain border cities. The charter established great benefits for Russian merchants: the customs duty for them was four times lower than for foreign traders. The Charter in every possible way encouraged a reduction in import operations and an increase in exports in order to attract additional funds to the treasury and create a positive trade balance for Russia, which was achieved at the end of the 17th century. Much of the credit for this belonged to A.L. Ordin-Nashchekin, Russian statesman under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. The government, under the influence of Ordin-Nashchekin, tried to carry out mercantilist policy, those. the policy of every possible enrichment of the state through foreign trade.

However, the possibilities of Russian international economic relations were noticeably hampered by the lack of convenient ice-free ports on the Baltic and Black Seas, so Russia’s search for access to the seas became a vital need at the end of the 17th century.

An important element in the formation of the all-Russian market was the creation in the country unified monetary system. Until the end of the 15th century, almost all the principalities of Rus' were engaged in minting coins independently - Tver, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod, etc. Prince Ivan III began to prohibit the minting of money for all princes who were part of a single state. He approved the Moscow money issue. The inscription appeared on Moscow coins: "Sovereign of All Rus'." But the parallel issue of money in Novgorod the Great continued until the time of Ivan IV. His mother Elena Glinskaya, widow of Vasily III, took certain steps towards creating a unified monetary system in 1534. She introduced strict rules for minting coins according to standard samples (weight, design), and violation of these standards was strictly punished. Under Elena Glinskaya, small silver coins were issued, on which a horseman was depicted with a sword in his hands - sword money. On dengas of larger weight, a warrior horseman was depicted striking a snake with a spear - penny money, which later received the name kopek. This money was irregular in shape, the size of a watermelon seed. Smaller coins were also issued - half-shells, or 1/4 kopeck, with the image of a bird, etc. Until the end of the 16th century, the year of issue was not indicated on the coins. Under Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich, they began to knock out the date “from the creation of the world.” At the beginning of the 17th century, Tsar Vasily Shuisky managed to issue the first gold Russian coins - kopecks and nickels, but they did not last long in circulation, turning into treasures.

Yet the most important factor in the unstable monetary circulation was the acute shortage of precious metals, and above all silver. Since the times of Kievan Rus, foreign coins have been used for monetary circulation for many centuries. In particular, under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, from 1654 on German and Czech thalers - round silver coins - the sovereign's mark was stamped in the form of a horseman with a spear or a double-headed eagle of the Romanov dynasty. T what coins were called efimok with a sign, they circulated in parallel with Russian coins. In addition to their independent circulation, small coins were minted from the efimka. From the very beginning, a fixed exchange rate was established: 1 efimok = 64 kopecks, i.e. that is exactly how many kopecks could be minted from one thaler. The actual silver content in one taler was only 40-42 kopecks.

By the middle of the 17th century, for a number of reasons, the state treasury was practically empty. The consequences of the Polish-Swedish intervention and the “Time of Troubles” also affected. For several years in a row there was a big crop failure, and to this we can add the plague epidemic of 1654-1655. Up to 67% of all government spending in the middle of the 17th century went to the maintenance of troops and constant wars: with Sweden (1656-1661) and with Poland (1654-1667).

To cover costs, the government introduced first inferior silver and then, in 1654, copper money with a forced official rate at which a copper penny was equal to a silver penny of the same weight. 4 million rubles of such copper money were issued. This immediately led to a depreciation of money and an increase in prices, since copper is much cheaper than silver. For one silver kopeck, at first they gave 4, and later - 15 copper kopecks. There were double prices for goods in the country. The state paid the servicemen and townspeople with copper, and required them to pay taxes in silver. The peasants refused to sell food with copper money. All this led to a decrease in the standard of living of the population, especially its lower strata, and to Copper riot in Moscow in 1662, which was brutally suppressed, and copper coins were withdrawn from circulation.

In the 17th century, the state’s desire to streamline the entire monetary and financial system intensified. This was primarily due to the fact that government spending on the maintenance of the administrative apparatus, the growing army (streltsy army, reiters, dragoons), and the huge royal court were constantly growing.

In 1680, Russia adopted first state budget where sources of income and expense items were indicated in detail. The bulk of the income came from direct taxes from the population. During this period, a census of peasants was carried out and it was established household taxation (from the yard or tax) instead of the previous one plowing tax “from the plow”, a conventional financial unit. This step made it possible to increase the number of taxpayers at the expense of slaves and other categories of the population from whom taxes were not previously taken. It should be noted that feudal lords and the clergy, as a rule, did not pay any taxes. Moreover, they also imposed their own taxes on the serfs.

A major source of budget revenue was indirect taxes on salt and other goods, as well as customs duties. A separate item of income was state monopolies state - the exclusive right to trade vodka within the country, and outside its borders - bread, potash, hemp, resin, caviar, sable fur, etc. The number of government goods included raw silk brought from Persia. Monopolies were often farmed out, which also supplemented the budget. For example, the richest Astrakhan fishing grounds in the country were in the hands of the treasury, which either farmed them out or rented them out, or managed them itself through loyal heads or kissers.

But all these sources of income did not cover the expenditure side, and the state budget remained deficit from year to year, which inevitably raised the question of the need for fundamental reforms in the country.

In the 17th century The most important qualitative shift is also taking place in trade - the formation of an all-Russian market. Before this, feudal fragmentation still remained economically: the country was divided into a number of local markets - regions within the country, between which trade exchanges took place. There were almost no stable trade relations. The isolation of local markets was reinforced by internal duties collected along the most important trade routes.

The merger of individual markets into one all-Russian market meant the establishment of a stable exchange of goods between individual regions.

This was a consequence of the beginning of the geographical division of labor. If districts exchange goods, then they produce different goods, which means they already specialize in producing certain goods for sale to other districts.

We have already discussed the regional specialization of fisheries. Regional specialization also begins in agriculture. The Middle Volga and Upper Dnieper regions became large areas of commercial bread production. The main areas of commercial production of flax and hemp (raw materials for textile industries) were the regions of Novgorod and Pskov.

IN AND. Lenin wrote that the true economic unification of the Russian principalities did not occur in the 15th century. but now, in the seventeenth century. This merger, he said, “was caused by the increasing exchange between regions, the gradually growing circulation of goods, the concentration of small local markets into one all-Russian market. Since the leaders and masters of this process were capitalists - merchants, the creation of these national connections was nothing more than the creation bourgeois connections." V.I. Lenin here emphasizes the bourgeois essence of the country’s economic unification, noting that it was from this time that bourgeois elements began to accumulate in the Russian economy.

Connections between individual regions were still weak, and this resulted in huge differences in prices for goods in different cities. Merchants profited from precisely this difference in prices, bought goods in one city, transported them to another and sold them much more than their cost, receiving profits from trade transactions of up to 100% or more on the invested capital. Such unequally high profits, as is known, are characteristic of the sphere of capital accumulation during the period of primitive accumulation.

A consequence of the weakness of trade ties was that fairs played a major role in trade. Fairs were the main form of medieval trade because a merchant could not travel around the country purchasing the goods he needed for retail trade at the places of their production. Such a detour would take several years. Merchants from different places came to the fair, which lasted several days a year, and each brought goods that he could buy cheaply at home. As a result, a full range of goods from different places was collected at the fair, and each merchant, having sold his goods, could purchase those he needed.

The largest fair in the 17th century. becomes Makaryevskaya - at the Makaryevsky Monastery near Nizhny Novgorod (Gorky).

Not only Russian merchants came here, but also Western European and Eastern ones. An important role was played by the Irbit Fair (the city of Irbit in the Urals), which connected the European part of the country with Siberia and eastern markets.

Foreign trade of Russia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. was quite weak.

Trade at that time was predominantly maritime, since the land transportation of goods was hampered by numerous duties on the borders of feudal states. Russia did not have access to the Baltic Sea, and therefore was virtually isolated from the West. This economic isolation was one of the reasons for the country's slow economic development. Therefore, Chancellor’s expedition played an important role for Russia. Setting off from England in search of the “northern passage” to India, Chancellor lost two of the three ships of his expedition and ended up in Moscow instead of India in 1553. English and then Dutch merchants began to penetrate this route into Russia following Chancellor, and trade with the West somewhat revived. In the 80s XVI century the city of Arkhangelsk was founded on the shores of the White Sea, through which the main trade with the West now took place.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century. About 20 ships a year came to Arkhangelsk, in the end - up to 150 ships. Lard, leather, potash, hemp, furs, cloth, metals, weapons, paper, wine, and luxury goods were exported from Russia through this port.

Trade with the East - Iran, India, Central Asia - was conducted mainly through Astrakhan. Cotton and silk fabrics were brought here from the East, furs, leather, and metal products were exported. The annual turnover of trade through Arkhangelsk was 10 times greater than through Astrakhan: Russia was oriented in foreign trade mainly to the West - there were goods that its development required.

The economic backwardness of Russia, the contradiction between the centralized state and the feudal organization of production, manifested itself in public finances. A lot of money was required to maintain the state apparatus. They are also necessary for the maintenance of the army: at that time in Russia, in addition to the noble militia, there were already regular regiments (regiments of the “foreign system”) and the Streltsy army, whose service was paid for in money and not in estates. In a country with a developed economy, the state has sufficient sources of income. In feudal Russia, income was insufficient to cover all government expenses. Moreover, these methods of receiving income to the treasury were of a feudal nature. One of the sources of replenishment of the treasury was monopolies and tax farming.

We have already talked about tax farming associated with the tsarist monopoly on trade in certain goods. The drinking business (sale of vodka) was also considered a royal monopoly. Vodka was sold at 5-10 times its original price. It was assumed that the difference should constitute state income. For this purpose, the sale of vodka was farmed out to merchants: they deposited the required amount of money into the treasury in advance, and then, by selling vodka, they tried to gain more for their benefit.

Such methods of replenishing the treasury enriched not so much the state as the tax farmers themselves.

Indirect taxes were widely practiced, and not always successfully. So, in the middle of the 17th century. the tax imposed on salt effectively doubled its market price. As a result, thousands of pounds of cheap fish, which the people ate during Lent, rotted, because it was impossible to salt cheap fish with expensive salt. There was a popular uprising, the “salt riot,” and the new tax had to be cancelled. Then the government decided to issue copper money with a forced exchange rate. However, the people did not recognize them as equal to silver ones. When trading, 10 copper rubles were given for a silver ruble. A new uprising took place - the "Copper Riot". The Streltsy, a city army armed with firearms, took an especially active part in this uprising, because they were paid in copper money for their service. The government also had to abandon copper money. They were withdrawn from circulation, and the treasury paid 5 and even 1 kopeck per copper ruble.

XVII century was marked by the most important event in the economic life of the country - the formation of the all-Russian market. In the country there was an increasingly noticeable deepening territorial division of labor. A number of areas specialized in the production of various industrial products.

In agriculture, a certain regional specialization also developed; agricultural farms began to produce products for sale. This contributed to strengthening economic ties between regions and the gradual merging of local markets into a single all-Russian market.

In the XV–XVI centuries. the center of trade gradually moved to Moscow. It was in Moscow in the 16th century. merchant class formed as a special class of city dwellers, playing an increasingly prominent role in the economic and political life of the country. Particularly eminent merchants and guests stood out here; there were about 30 of them. This honorary title was received from the tsar by those who had a trade turnover of at least 20 thousand rubles. per year (or about 200 thousand gold rubles on the scale of the beginning of the 20th century). In the XVI–XVII centuries. in Russia the process of initial capital accumulation specifically in the field of trade. Later, merchant capital began to penetrate into the sphere of production, rich merchants bought craft workshops and industrial enterprises. Along with patrimonial and state-owned manufactories, merchant manufactories appeared, which used the labor of free townspeople, quitrent peasants released to latrine trades, and also attracted foreign craftsmen.

In the XVI–XVII centuries. Russia has become more actively develop foreign trade. Even when Vasily III trade agreements were concluded with Denmark, with Ivan IV Strong ties have been established with England. English merchants were given great privileges in trade, which was carried out practically without duties for both sides.

Important element education all-Russian market was the creation of a unified country monetary system. In the 17th century the state's desire to streamline monetary and financial system. In 1680, Russia adopted first state budget, where sources of income and expense items were indicated in detail. The bulk of the income came from direct taxes on the population. During this period, a census of peasants was carried out and household taxation from the yard, or tax, was established instead of the previous personal tax on the plow, a conventional financial unit. This step made it possible to increase the number of taxpayers at the expense of slaves and other categories of the population from whom taxes were not previously taken. Feudal lords and clergy, as a rule, did not pay any taxes. Moreover, they imposed their own taxes on serfs. A major source of budget revenue was indirect taxes on salt and other goods, as well as customs duties. A separate source of income was the state's state monopolies - the exclusive right to trade vodka within the country, and outside it - bread, potash, hemp, resin, caviar, etc. Monopolies were often farmed out, which also replenished the budget. But all these sources of income did not cover the expenditure side, and the state budget remained deficit from year to year.